I’ve been playing with Activiti. It’s an open source, BPMN 2.0 compliant business process engine. The project is sponsored by Alfresco, who hired Tom Baeyens and Joram Barrez, the founders of jBPM, to create the Apache-licensed engine (take a look at the rest of Activiti’s all-star cast).

The first thing I did was head over to Activiti’s site and read through the user guide. I followed the tutorial and got a standalone instance of Activiti going with very little fuss. The concepts and terminology aren’t terribly different from jBPM, so if you’ve used jBPM, you’ll be familiar with the basics of Activiti in no time. The user guide is well-written so I urge everyone to start there.

Last week, Alfresco released a preview release of their Community product, labeled 3.4.e. This release, which I stress is only for preview purposes, was made available to let everyone get a first look at Alfresco’s integration of Activiti. If you watched the screencast showing an Alfresco workflow based on Activiti you may have thought, “Gee, that looks just like a jBPM-based workflow,” and you’re right–from a user standpoint, it is nearly identical. The difference, of course, is how the processes are described and the underlying implementation that executes the processes.

The screencast showed that the end users won’t see much of a change. That’s good, but I was anxious to find out how big a deal this transition will be from a developer’s perspective. The 3.4.e release gave me the perfect opportunity to dig in. I decided to take the examples from the Advanced Workflow chapter in the Alfresco Developer Guide (2008, Packt) and make them work with Alfresco’s embedded Activiti engine in 3.4.e. In this post, I’ll talk about how that went and I’ll give you the code so you can try it out yourself.

The code that accompanies this blog post includes the same set of four workflows implemented both in jBPM and Activiti as well as a readme that explains how to install and run everything. I’ll let you inspect that to see what the exact differences are rather than go over them here. Instead, I’ll spend the rest of the post covering the major differences in general.

Before we go any further, I guess we should have a quick terminology discussion. First, in jBPM, everything is a node. Specialized node types do different things like joins, splits, decisions, wait-states, sub-processes, and enclose tasks that get assigned to humans. In Activiti (and really, in BPMN) there are essentially events (start, stop, timer), tasks, and gateways. Of course, I’m simplifying greatly here–you should read the spec and the Activiti user guide. The important thing to note for people coming from jBPM is that in Activiti a “task” might be something a human does (“userTask”) or it could be automated (“scriptTask”, “serviceTask”, etc.). In jBPM connections between nodes are called “transitions” while in Activiti they are called “sequenceFlows”.

Designing Processes

I use Eclipse, so the first step was to get the Activiti BPMN 2.0 Designer plug-in working. Installation is well-documented on the Activiti wiki and it installs just like any other Eclipse plug-in, so it went fairly smooth. I had some sort of dependency conflict that I had to deal with, but nothing major.

All in all, designing processes in Activiti works just like it does in jBPM. The tool is different, but you’re still laying out a business process graphically, connecting steps in the workflow, and setting properties on those objects.

There are some known issues with the Designer that made creating and editing processes painful at times. I’m not going to call every one of those out in this post because this is a preview release–I expected to work through a few bumps. I will warn you of a few to hopefully save you some time:

- You cannot save the diagram until it is syntactically correct. This means the BPMN 2.0 XML will not get generated until the diagram is correct. On a new process, when the editor complains about the diagram, you’d kind of like to just drop in to the XML source and fix what needs fixing. If that’s what you want to do, you have to open the .activiti file in the XML editor, make the change, re-open in the diagram, and then make a change and save to force the generation of the BPMN 2.0 XML.

- You cannot change things like IDs, names, form keys, and task assignment in the BPMN 2.0 XML. You have to change these in the Activiti diagram. If you change the BPMN 2.0 XML the settings in the Activiti diagram will overwrite the BPMN XML. This doesn’t sound like a big deal until you come across the next issue.

- There is a known problem enabling the properties for an object in the diagram: clicking an object in the diagram doesn’t refresh the properties view. I worked around it by first clicking some other tab in the properties view, then double-clicking on the object (and sometimes repeating that) until the properties view refreshed with the appropriate property set.

Again, I didn’t expect everything to be fully functional, so I am not complaining. I just want you to have your expectations properly set when you play with this on your own.

I should mention that the overall look-and-feel of the Activiti Designer seems a lot crisper and more visually appealing than the JBoss Graphical Process Designer (GPD) Eclipse plug-in. As an example, I loved the alignment helper rules. And I liked that you can bend sequence flows.

Adding Business Logic to Processes

My goal was to take four Alfresco jBPM processes and port them to Activiti. The first three are variations on Hello World. The fourth is a more real-life process that is used to review and approve whitepapers. In the book, the Publish Whitepaper workflow uses an action to set properties on the approved whitepaper. And I show how to combine a wait state with a mail action and a web script to allow third parties without direct access to Alfresco to participate in a workflow. For the initial cut at this exercise, I skipped all of that. For now, I really wanted to focus on the basics of the workflow engine. But the state idea and the web script interaction are interesting so I’ll do that later and will provide the update in a future blog post.

Challenge 1: Alfresco JavaScript in automated steps

The first problem I came to was how to handle workflow steps that have no human intervention. In jBPM those steps are implemented as nodes. Alfresco JavaScript can live inside events within the node or on transitions between nodes. Tasks assigned to users are typically enclosed in a task-node. In Activiti, tasks assigned to users are called userTasks. All of Alfresco’s sample Activiti workflows consist entirely of userTasks. But Activiti includes several node types that aren’t user tasks: a scriptTask uses JavaScript or Groovy to implement its logic and a serviceTask delegates to a Java class. My helloWorld processes consist entirely of automated steps, so a scriptTask sounded good to me. The problem was that scriptTask uses Activiti’s JavaScript implementation, not Alfresco’s JavaScript. So doing something simple like invoking the “logger” root object doesn’t work in a scriptTask.

Fine, I thought, I’ll use one of Alfresco’s listener classes to wrap my logger call and stick that listener in the scriptTask. But that didn’t work either because in the current release Alfresco’s listener classes don’t fully implement the interface necessary to run in a scriptTask.

After confirming these issues with the Activiti guys I decided I’d put my Alfresco JavaScript in listeners either on a userTask or on a sequenceFlow (we called those “transitions” in jBPM) depending on what I needed to do. Hopefully at some point we’ll be able to use scriptTask for Alfresco JavaScript because there are times when you need automated steps in your process that can deal with the Alfresco JavaScript root objects you’re used to.

Challenge 2: Processes without user tasks

As I mentioned, my overly simple Hello World examples are nothing but automated steps. I could implement those without userTasks by placing my Alfresco JavaScript on sequenceFlows. But Alfresco complained when I tried to run workflows that didn’t contain at least one user task. I didn’t debug this, and it is possible I could have worked through it, but I decided for now, the Activiti versions of my Hello World examples would all have at least one userTask.

Challenge 3: Known issue causes iBatis exceptions

In 3.4.e, there is a known issue in which user tasks will cause read-only iBatis exceptions unless you set the due date and priority. Search my examples for “ACT-765” to find the workaround.

Challenge 4: Letting a user pick between multiple output paths

Suppose you have a task in which a human must decide whether to “Approve” or “Reject”. In Alfresco jBPM, you’d simply have two transitions and you’d set the label for those transitions in a properties bundle. In Alfresco Activiti that is handled a bit differently. Instead of having two transitions leaving the task, you have a single transition to an “exclusive gateway” (called a “decision”, in polite company). The task presents the “outcome” options–in this case “Approve” and “Reject”–to the user in a dropdown, as if it were any other piece of metadata on the task. Once the user picks an outcome and completes the task, the exclusive gateway checks the outcome value and takes the appropriate sequence flow. This difference will impact your business process logic, your workflow content model, and your end user experience so it is a significant difference.

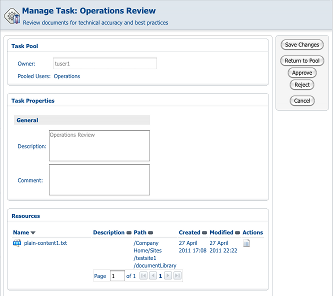

For comparison, here’s what this looks like in the Alfresco Explorer UI for jBPM (click to enlarge):

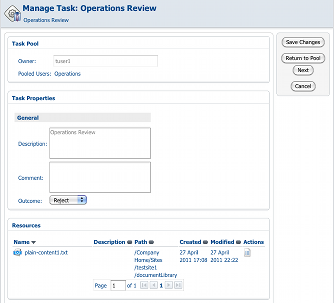

And here is what it looks like in the Alfresco Explorer UI for Activiti (click to enlarge):

So in Explorer, with jBPM, the user can just click “Approve” or “Reject” while in Activiti, the user must make a dropdown selection and then click “Next”.

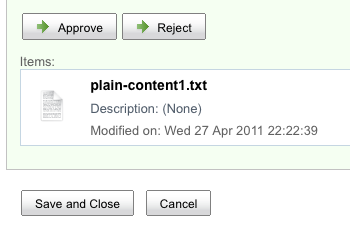

Here is the same task managed through the Alfresco Share UI for jBPM:

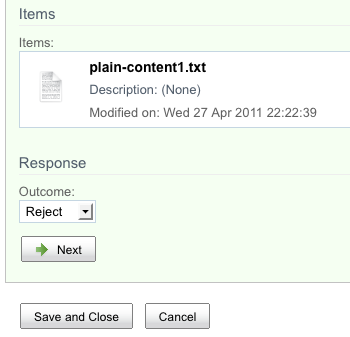

Versus Alfresco Share for Activiti:

Similar to the Explorer differences, in Share, with jBPM, the user gets a set of buttons while with Activiti, the user makes a dropdown selection.

One open question I have about this is how to localize the transition steps for Activiti workflows if the steps are stored as constraints in the content model. On a past client project we implemented a Share-based customization to localize constraint list items but our approach won’t work in Explorer. Maybe the Activiti guys can help me out on that one.

Exposing Process to the Alfresco User Interface

And that brings us to user interface configuration. Overall, the process is exactly the same. First, you work on your process definition, then you create a workflow content model. Once the workflow content model is in place, you expose it to the user interface through the normal Alfresco user interface configuration approach. For the Explorer client that means web-client-config-custom. For the Share client that means share-config-custom. Labels, workflow titles, and workflow descriptions are localized via properties bundles.

One minor difference is that in jBPM, task names are identical to corresponding type names in your workflow content model. In Activiti, a userTask has an attribute called “activiti:formKey” that is used to map the task to the appropriate content type in the workflow content model.

Assigning Tasks to Users and Groups

The out-of-the-box workflows for both jBPM and Activiti show how to use pickers to let workflow initiators assign users and groups to workflows. My example workflows use hardcoded references rather than pickers so that you’ll have an example of both approaches. In my Hello World examples, I assign the userTask to the workflow initiator. This is done by using the “activiti:assignee” attribute on userTask, like this:

<userTask id="usertask3" name="User Task" activiti:assignee="${initiator.properties.userName}" activiti:formKey="bpm:task">

If you need to use a more complex expression there’s a longer form that uses a “humanPerformer” tag. See the User Guide.

In the Publish Whitepaper example I use pooled group assignment by using the “activiti:candidateGroups” attribute on userTask, like this:

<userTask id="usertask7" name="Operations Review" activiti:candidateGroups="GROUP_Operations" activiti:formKey="scwf:activitiOperationsReview">

Again, if you need to, there’s a longer form that uses a “potentialOwner” tag.

In my jBPM examples I use swimlanes for task assignment. I didn’t get a chance to use the equivalent in Activiti.

Deploying Processes

In standalone Activiti there are multiple options for deploying process definitions to the engine, including uploading a BAR (Business Archive) file into the running engine. I couldn’t find the equivalent of that in Alfresco’s embedded Activiti implementation or the equivalent of the jBPM deployer servlet, so for this exercise I used Spring configuration for both Activiti and jBPM processes. I hope by the time the code goes into Enterprise there will be a dynamic deployment option because that’s really helpful during development.

Workflow Console

Alfresco’s workflow console is a critical tool for anyone doing anything with advanced workflow. It has always been a puzzle to me as to why the workflow console (along with others) can only be navigated to directly using an unpublished URL. That head-scratcher still remains, but rest assured, all of your favorite console commands now work for both jBPM and Activiti workflows.

Summary

I hope this post has given you a small taste of the new Activiti engine embedded in Alfresco. I haven’t spent any time talking about the higher level benefits to Activiti. And there are many more details and features I didn’t have time to go into. My goal was to give all of you who have experience with Alfresco jBPM some start at getting your head around the new option for advanced workflow.

If you haven’t done so, grab a copy of Alfresco 3.4.e, download these examples, and play around. The zip is an Eclipse project that will deploy the workflows and associated configuration to your Alfresco and Share web applications via ant. The included readme file has step-by-step directions for running through each jBPM and Activiti example.

It is entirely possible that I’ve done something boneheaded. If so, do let me know so that all of us can benefit.

Resources

- Download the Alfresco 3.4.e preview release

- Download the code that accompanies this blog post

- Read the Activiti User Guide

- Join the conversation in the Activiti Forums. Ask questions here about both standalone Activiti and Activiti embedded in Alfresco.

- Read a brief description of the Activiti integration with Alfresco