Last Fall, just before the Developer Conference in New York City, Alfresco approached Metaversant with a small project–they needed a web site to share presentations from the DevCon sessions and other events. There are several generic slide-sharing sites out there–Alfresco and I have both used SlideShare for that sort of thing pretty extensively. But Alfresco was looking for something they could have complete control over, plus they were looking to exercise their new Web Quick Start offering. So I rounded up a sucker–I mean a collaborator–named Michael McCarthy from over at Tribloom, and we knocked it out.

Although it makes good marketing sense for Alfresco to use its own offering for the site, I do think the “private presentation-sharing” use case is also generally applicable to many other businesses out there. Technology companies, of course, but also any company with a large sales force or even more modest extranet needs could benefit from a solution like this. SlideShare is great when what you want to share is public. When presentations need to be securely shared, many companies use expansive portals to share sales collateral, marketing presentations, or company communications, but those often come with a very low signal-to-noise ratio. The solution we built–we call it “DeckShare”–is laser-focused on one thing: Making it easy for content consumers to find the presentations they need, quickly.

DeckShare is built on top of Alfresco’s new Web Content Management (WCM) offering called Web Quick Start. Honestly, Web Quick Start, as the name implies, provides a good starting point for building a dynamic web site on top of Alfresco, and the sample site was so close to what a basic slide-sharing site needed, we didn’t have to do a whole lot of work. Even so, if you want to do slide-sharing on top of Alfresco, you can save even more time by starting with DeckShare.

I thought it might be cool to walk you through how we got from the Web Quick Start sample app to DeckShare as a way of getting you familiar with Web Quick Start and to help you understand how DeckShare works in case you want to use it on your project.

Some of this write-up is also included in the “About” page within the DeckShare site. Alfresco is currently branding DeckShare to meet their needs so I have no idea if the About page will still be there when the site goes live, so I may or may not be repeating myself somewhat.

What is DeckShare?

Alfresco’s DeckShare implementation isn’t live yet, so let me give you the nickel tour. DeckShare is a solution for quickly creating a self-hosted presentation-sharing site on top of Alfresco without having to write any code. DeckShare lets non-technical users manage and categorize presentations that are then consumed by end-users. End-users can find presentations by browsing one or more hierarchies (“Topics”, “Events”, “Audience”, for example), performing a full-text search, or by browsing the list of the latest and “featured” presentations. Content managers can associate presentations with “related” presentations and can link supporting files with a presentation.

In this solution, Content Managers are a different set of users than Content Consumers. As it stands, the solution doesn’t accomodate user-contributed presentations, unlike SlideShare. Obviously, it could be customized to do that.

Here’s what it looks like when a Content Manager edits the metadata for a particular presentation (click the image for full-size):

Those familiar with Alfresco can tell from the screenshot that Content Managers use Alfresco Share as the “content administration” user interface. Optionally, you could turn on Alfresco’s Web Editor Framework and allow Content Managers to edit the site in-context, but that will require some minor tweaking if you go that route. Using Share for content administration works really well. What started out as a team collaboration web app has essentially turned into Alfresco’s uber client.

Now let’s take a look at the Content Consumer user interface:

If you’ve seen either of the sample Web Quick Start applications, the layout will look familiar. The home page includes a featured content carousel, a recently added document list, and a document category tree. We’re using a different carousel widget than the Web Quick Start sample apps and the category tree is also something we’ve added.

The set of categories is almost completely arbitrary and can be managed by DeckShare administrators. In fact, if you are running DeckShare on top of an existing Alfresco repository, you can specify the subset of categories you want to show in the category tree. When you click a specific category, the resulting page looks like this:

The category page shows only the presentations for a specific category and features the same category tree browser that appears on the home page.

Ultimately, an end-user will either download a presentation or they’ll click on the details page link to learn more. The details page, shown below, shows high-level metadata about the presentation, supporting files that accompany the presentation, related presentations, and a flash-based document preview. The flash-based preview allows end-users to browse the presentation without downloading the entire file.

That’s really it from a Content Consumer perspective. The site also has full-text search and that page is very similar to the category list page.

From a Content Manager’s point of view, DeckShare, like all Web Quick Start sites, is built on concepts familiar to anyone who has built or managed a web site: A site consists of collections of assets that get categorized and tagged and then presented in various ways across one or more pages. The look-and-feel of the end-user web site can be completely customized to match client branding needs. And, both the metadata model and category hierarchy can be extended to support specific client requirements.

Assets are stored in Alfresco’s Document Management repository and managed through the Alfresco Share User Interface. Alternatively, Content Managers have several other options for getting presentations into the repository, including FTP, drag-and-drop via Windows Explorer or Mac Finder, emailing content into the repository, drag-and-drop from within Microsoft Outlook or Lotus Notes, or saving directly from Microsoft Office as if the repository were a Microsoft SharePoint Server. Regardless of how the files arrive, Alfresco automatically takes care of creating thumbnails and PDF renditions of the presentations.

What is Web Quick Start?

Web Quick Start is a sample web application built with Spring, Spring Surf, and Apache Chemistry’s OpenCMIS library. It is essentially a sample web application that sits on top of the Web Quick Start API (Java), some presentation tier services, some repository tier services, and an extended content model.

Assets are stored in Alfresco’s Document Management repository and managed through the Alfresco Share User Interface. That means you can use all of the familiar building blocks present in the repository such as custom types and aspects to model your data, behaviors, and web scripts.

The presentation tier uses Alfresco Surf to lay out pages and to define regions on those pages. Regions get their content from presentation tier web scripts. What’s different with Web Quick Start as opposed to previous Surf-based web application examples is the use of the Apache Chemistry OpenCMIS library. Instead of using Surf’s object dispatcher to load and persist objects, the Web Quick Start API uses OpenCMIS to make CMIS requests between the front-end and the repository tier. There are some places where the Web Quick Start API uses non-CMIS web scripts, so it is not a pure CMIS implementation, however.

The Web Quick Start API is exposed to the Alfresco JavaScript API and Freemarker API on the presentation tier, so everything you’ve already learned about Spring Surf is immediately leverageable when you build the front-end. However, if you’ve decided on another framework, you can still use the Web Quick Start API, the services, the content model, and Share for editing content. For example, Metaversant recently worked with a client that chose Spring 3 and Apache Tiles for the front-end because that was their standard, but they used Web Quick Start for everything else from the API, back.

Web Quick Start sites have a flexible deployment configuration which can be boiled down to “single-server” or “multi-server”. In the single-server approach, the same Alfresco server is used for content authoring and content serving whereas in the multi-server approach, Alfresco’s transfer service is used to move content from the “authoring” or “editorial” web server to the “Live” server (it doesn’t have to be one hop, you could throw in one or more “QA” servers as well if you want to, for example).

High-level steps

Web Quick Start is meant as a starter application. It’s functional out-of-the-box, but you’re expected to use as much (or as little) of it as you need. Here are the high-level steps we took to reshape the starter app into DeckShare.

Step 1: Extend the content model

Web Quick Start has a simple content model that provides for articles, images, and user feedback. For DeckShare, we added two new aspects to our own model. One is used to associate a presentation with zero or more related presentations. The other is used to associate a presentation with zero or more supporting files (like source code downloads). At some point we may also add an aspect to track fine-grained event metadata such as session time, speaker, etc. Extending the model with your own aspects is pretty easy–it’s some XML to define the model and then some XML to expose the model to the Share interface.

Step 2: Set up site sections and collections

Web Quick Start has a default folder structure that lives in the Document Library of the Share site being used to manage the content. Within that there is one folder for editorial content and one for live content. Then, it breaks down into “section” folders for site assets (publications, in this case) and collections. Each section will typically map to a section of a site and will therefore show up in the site navigation, but you can exclude sections from the navigation.

Every section folder has a set of collections. A collection is an arbitrary grouping of site assets. Collections can either be static or query based. For a static collection, Content Managers choose the assets that belong in that section with standard Share “picker” components. For a query-based collection, Content Managers can use either CMIS Query Language or Lucene to define queries that identify the assets that are included in the collection. Either way, from the Web Quick Start API, a developer just says, “Give me this collection and let me iterate over the assets in it” to produce a list of the assets in a collection.

There are two sample data sets that ship with Web Quick Start. One is for a Finance example site and the other is for a Government site. We started with the Finance site (the choice was based on luck–there’s really not much of a difference between the two other than images and content). Once we imported the sample site, we deleted all of the sample content and then tweaked the collection definitions. The “latest” collection, for example, contains the most recently-added presentations. The “featured” collection is static out-of-the-box, but we wanted it to be dynamic. So, we simply edited the collection metadata to add a query that returns all of the presentations that have been categorized as “Featured”. Alfresco runs the query periodically so that Content Consumers don’t take the performance hit when the page is rendered.

The carousel works similarly. We wanted Content Managers to be able to specify which presentations appear in the carousel simply by applying the “Carousel” category to the content from within Share, so the carousel collection looks for content that has that category applied.

The other tweaks we made to the sample data set include telling Web Quick Start which rendition should be used for the various thumbnails in the site. We added a new rendition definition for the images shown in the carousel and a new rendition for the thumbnails used everywhere else. Web Quick Start has its own rendition definitions, but the thumbnails aren’t set to maintain the aspect ratio when they are resized and that looks a little weird for images of thumbnail presentations, hence the need for our own.

Step 3: Customize page layout

Once we had some sample data in place and our collections defined, it was time to start laying out the pages. As luck would have it, the requirements matched up fairly closely to the layout of the sample financial site. Surf pages and templates are used for layout, but you don’t have to be a Surf Guru to make changes. Surf templates are just FreeMarker, after all. Other than minor re-arranging, our template modifications were limited to adding additional regions to existing templates.

Once you define your page layouts, you use metadata on the section folders to tell Web Quick Start which page layout to use for a given piece of content. The mapping is type-based. For a given section, you might say, “All instances of ws:indexPage in this section should use the ‘list’ template” which is expressed like this:

ws:indexPage=list

The template mapping is hierarchical. That means for a given piece of content, Alfresco will look at that content’s section for the template mapping but if it isn’t specified, it will look in that section’s parent, and so on. So if we specify:

cmis:document=publicationpage1

in a high-level section folder, all instances of cmis:document in child sections will be layed out using publicationpage1 unless it is overridden by a child section.

Note: If you are familiar with Surf, don’t be confused by the use of the word “template” here. It’s used by Web Quick Start in a generic sense. In the example above, “list” and “publicationpage1” are actually page data objects in Surf. For the Metaversant client that used Spring 3 and Tiles, for example, the template mapping specified which Tile definition to use.

Step 4: Add custom components

We spent most of our time on components. In Surf, components are implemented as web scripts. A web script implements the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern. In this case, controllers are JavaScript. Here’s what one of the controllers looks like:

model.articles = collectionService.getCollection(context.properties.section.id, args.collection);

if (args.linkPage != null)

{

model.linkParam = '?view='+args.linkPage;

}

This one is simply grabbing a collection of articles and a parameter and sticking them on the model for the FreeMarker-based view to pick up. Behind the scenes, the Web Quick Start API is making RESTful calls to the repository to retrieve (and cache) objects. This is a typical controller–in this app, most of the controllers are less than 10 lines long.

Web Quick Start already has components for different types of content lists. So doing something like the carousel was relatively easy: The collection service returns the “carousel” collection and a FreeMarker template dumps the collection metadata into a list that the YUI carousel control can grok.

We had a couple of places where we had to write our own components. One was the Categories component and another was the Related Presentations component. The Categories component is rendered using a YUI tree control. It gets its data by invoking a Surf-tier web script which, in turn, invokes a repository-tier web script that returns a list of category metadata as JSON. YUI then styles the data as a tree.

The Related Presentations component similarly invokes a repository-tier web script, but its JSON contains only node references. It then asks the Web Quick Start API to convert those into CMIS objects. That allows us to take advantage of the cache if the object has been loaded before, and it means we can re-use the Web Quick Start view templates that already know how to format lists of CMIS objects.

But wait, there’s more

Web Quick Start also has a user feedback mechanism that you can use for comments, “contact us” forms, and, at some point, ratings, but none of that was a requirement for this solution at the time we built it. The capability is there, so we’ll probably expose it at some point. Refer to the wiki for more information on the user feedback functionality.

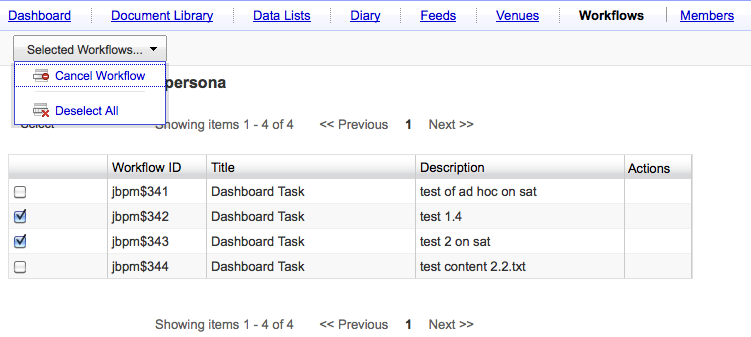

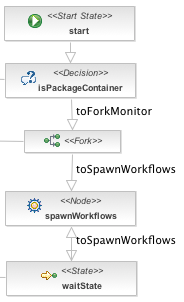

There’s also a workflow that is used to submit content for review. Once approved, the content is queued up for publishing to the live site. The workflow is the same jBPM engine you are probably already familiar with so the process can be modified to fit your needs.

Although it is a new product and there are still a few hitches here and there, I was happy with Web Quick Start and the time it saved for building a site like this. I’m looking forward to seeing its continued evolution.

DeckShare is a simple site. There is a lot more that could be done with it and, based on client demand (or contributions from others, hint, hint), new features will be added over time. I think it’s a good example of what you can do quickly with Web Quick Start.

Hopefully, this write-up gave you some ideas you can use on your own projects. If you want to dive deeper into the Web Quick Start web application, check out the Web Quick Start Developer Guide on the Alfresco wiki. Feel free to grab the DeckShare source from Google Code and use it on your own projects.

If you’re interested in major customizations to DeckShare or you have a project that might be a fit for Alfresco Web Quick Start, let me know.

The combination of the wait state and the spawn workflows node in the business process with the custom rule action that signals the wait state creates a cool little “interrupt” loop: The process spawns workflows for folder children, then waits until more children arrive, then spawns workflows for those children, and so on until someone kills the workflow.

The combination of the wait state and the spawn workflows node in the business process with the custom rule action that signals the wait state creates a cool little “interrupt” loop: The process spawns workflows for folder children, then waits until more children arrive, then spawns workflows for those children, and so on until someone kills the workflow.