It is often necessary to perform bulk operations against the data in your Alfresco repository. Frequently, writing a quick script, rather than a full application, is the best approach. Sometimes those scripts need to be scheduled, like with a cron job, or given to power users to run ad hoc.

It is often necessary to perform bulk operations against the data in your Alfresco repository. Frequently, writing a quick script, rather than a full application, is the best approach. Sometimes those scripts need to be scheduled, like with a cron job, or given to power users to run ad hoc.

The good news is that there are many options available depending on what you need to do and personal preference.

All of these options can be used to develop full-blown applications, but the focus in this post is on how well each option works specifically for the scripting use case.

JavaScript Console

License: Apache 2.0

Link: https://github.com/share-extras/js-console

Install: Repo and Share AMPs, requires restart

The JavaScript Console provides a user interface within Share to interactively run server-side scripts that leverage the Alfresco JavaScript API. The UI features syntax highlighting and code completion.

This is a must-have tool for both developers and administrators. It is the fastest way to perform bulk tasks or to test out JavaScript logic before using it in something harder to debug or change, such as in the controller of a web script. I install this on every server I touch. I suppose that, eventually, as Share falls out of favor, this will be less of a go-to option, but, for now, it is essential.

The JavaScript Console is only available to administrators, so this is not an option if you are developing something that will be invoked by non-admins.

Apache Chemistry CMIS Workbench

License: Apache 2.0

Link: https://chemistry.apache.org/java/developing/tools/dev-tools-workbench.html

Install: On your own desktop, no server config/restart required

The Apache Chemistry CMIS Workbench is a desktop application that uses pure CMIS calls to communicate with the repository. It contains a lot of useful features such as a CMIS Query Language console, a node browser, a data dictionary browser, and a Groovy console. The Groovy console is similar to the JavaScript console in that it can be used to quickly script repetitive tasks, but instead of JavaScript it uses Apache Groovy. If you aren’t familiar with Groovy but you know Java, you can use Java in the Groovy console–Groovy is a JVM language and is happy to interpret your Java syntax.

This tool is particularly useful if you are writing code that leverages CMIS. If you can do it in the Workbench you can be confident you can do it from your CMIS-based application. However, it is also useful when you just need to execute some repetitive tasks, especially if the server in question does not have the JavaScript Console installed.

Unlike the JavaScript Console, however, you are limited by what is supported in the CMIS specification. For example, you cannot manage users, groups, or workflows, just to name a few. It is pretty much limited to documents, folders, and items (content-less objects). Custom content models, however, are fully-supported.

The Swing-based UI of the workbench has a face only a mother could love so this is definitely not something you’d put in the hands of typical end-users.

Apache Chemistry cmislib (Python client)

License: Apache 2.0

Link: https://chemistry.apache.org/python/cmislib.html

Install: Client library, no server config/restart required

If what you need to do is covered by the CMIS specification but you prefer Python, then Apache Chemistry cmislib might be a good choice. It is a client library that you can use from your own Python scripts and applications. For example, if I need to generate a bunch of folders or documents, I’ll often just write a quick Python script to do it.

The library has the same limitation as the Workbench in that it only makes CMIS calls, but if that’s all you need it should work well. The current release requires Python 2.7 but a new release that supports Python 3.x is being tested now.

If you are giving the script to power users who might want to make tweaks this can be a good choice if they already have Python installed.

Apache Chemistry OpenCMIS (Java client)

License: Apache 2.0

Link: https://chemistry.apache.org/java/opencmis.html

Install: Client library, no server config/restart required

Rounding out my CMIS-related recommendations is Apache Chemistry OpenCMIS. Like cmislib, it is a client library, but this one is written in Java and is much more mature and more widely-used. For quick scripts you can use Groovy on the command-line to make CMIS calls against Alfresco via OpenCMIS. Often, I already have my Java IDE open anyway, so it can be just as quick to write a little runnable Java class that uses OpenCMIS to carry out some tasks.

I use Groovy scripts and OpenCMIS when I want to automate tasks that power users are going to run from the command-line that they may want to tweak, but who do not have Python installed.

When a single script needs to perform operations that are a mix of CMIS and non-CMIS, I use Groovy’s HTTP client to call the Alfresco REST API (more on that, below).

Alfresco Web Script Framework

License: LGPL v3

Link: https://docs.alfresco.com/5.2/concepts/ws-framework.html

Install: For quick scripts, copy to Data Dictionary

Strictly speaking, web scripts weren’t built to be a “quick scripting” option, but they’ll work in a pinch. Basically, you just write a web script that does what you need it to do, but instead of packaging the web script into an AMP like you would for a production extension, you deploy the web script to the running repository by copying the web script related files into the Data Dictionary’s Web Scripts folder. The next step is to refresh the web scripts via the web script console. After that the web script can be invoked in a browser, via CuRL, or Postman.

Just like the JavaScript Console, you are limited to what the Alfresco JavaScript API can do, but that is definitely a broader set of capabilities than a CMIS-based solution.

Files in the Data Dictionary can only be edited by administrators, so if the folks running this script need to make changes and aren’t administrators, this won’t work. You can always build that flexibility into the web script and let them control various options by what they pass to the web script.

For more information on Web Scripts, see the documentation link above or check out my tutorial.

Alfresco Client-side JavaScript API

License: Apache 2.0

Link: https://github.com/Alfresco/alfresco-js-api

Install: Node Package Manager

A relatively new kid on the block is the Alfresco Client-side JavaScript API, aka, alfresco-js, which is part of the Alfresco Developer Framework (ADF). Of course you can use it to develop custom user interfaces in your favorite JavaScript framework, but you can also use it for quick scripting needs. For example, you could write a Node.js script and run it from the command-line.

The alfresco-js library relies on the Alfresco REST API that was created in 5.2, so if you need to work with an older Alfresco version, this isn’t an option. The alfresco-js library and the REST API are both under active development, so there could be gaps and some instability, but it is still worth taking a look, especially if you are already invested in the Node.js and NPM ecosystem.

Alfresco Content Services REST API (And others)

License: LGPL v3

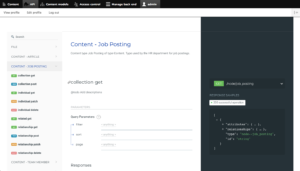

Link: https://api-explorer.alfresco.com

Install: Your favorite REST client

Last, but not least, is the Alfresco Content Services REST API. If none of the other options in this list appeal to you, grab your favorite REST client or import your preferred scripting language’s HTTP client library, head over to the Alfresco API Explorer, and get busy.

As mentioned above in the alfresco-js description, this option relies on Alfresco 5.2 or higher (5.2.d Community Edition, distributed as 201612).

If the Alfresco Content Services REST API doesn’t have what you need or you aren’t yet running 5.2 or higher, you could always hit the CMIS browser (JSON) binding, the CMIS atompub (XML) binding, out-of-the-box web scripts, or custom web scripts.

Depending on what you need to do, using a lower-level REST API may not be the fastest option in terms of development time because instead of working with higher-level wrapper classes it is up to you to issue the REST calls and parse the responses.

Summary

Hopefully you see some options in the above list that will work for you and your environment. I definitely recommend you get a few of these in place now (especially the JavaScript Console) because if you ever need them in a hurry (oh, if this keyboard could talk!), you’ll want to have a quick scripting option you are comfortable and proficient with.

Photo Credit: Quality Quick Cleaning by GmanViz, by-nc-nd 2.0

Friday, May 25, 2018 was an auspicious day. You may remember it as the crescendo in the wave of GDPR-compliance related email notifications because that was the day everyone was supposed to have their GDPR act together. For those of us in the Alfresco Community, it was also the day that the Add-ons Directory died (or, more correctly, was killed). In fact, the two are directly related. More on that in a minute.

Friday, May 25, 2018 was an auspicious day. You may remember it as the crescendo in the wave of GDPR-compliance related email notifications because that was the day everyone was supposed to have their GDPR act together. For those of us in the Alfresco Community, it was also the day that the Add-ons Directory died (or, more correctly, was killed). In fact, the two are directly related. More on that in a minute. Alfresco Software, Inc. has announced that

Alfresco Software, Inc. has announced that